How I Design a Novel Unit for Middle School

So Much More Than Picking the Perfect Book

I think all new English teachers love the idea of the novel study. I did. I still do. However, I have picked up some skills and strategies along the way that have made my novel units much more enjoyable for both me and my students. In my first year of teaching in 2010, I was instructed by my district pacing guide to teaching Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry by Mildred Taylor to my sixth-grade students. I was at the district alternative middle school that involved a heavily transient population that struggled with reading. I think we studied that book for almost 3 months because we couldn’t move as a group through the novel. I had an idea in my head, I wanted to finish the idea to the end, and I was determined to manifest that moment of talking about a book happen in my first-year classroom. It didn’t happen. Now, it is a story I tell my pre-service teachers when they come into my room to observe my classroom during novel units. A novel study should never be a tool for torture.

I still teach Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry; however, my novel units are designed completely different from when I started teaching. I also know when it is okay to give up on something if it is not working. No teacher I know wants to be pegged as a “book quitter,” but there are times when we, as teachers, need to quit books, practice, and strategies that we have been doing to discover a deeper level of learning on the other side. Perhaps one of the best parts about being a teacher of English is the infamous novel study unit. From choosing books to share with students to figuring out how to shape the ins and outs of each day of class, the novel unit remains a joy to teach and a complicated mess. This post will walk you through all the things I think about when it comes to teaching a novel to a group of students. I also throw in some examples at the end of the post for you to check out in both general and accelerated classes.

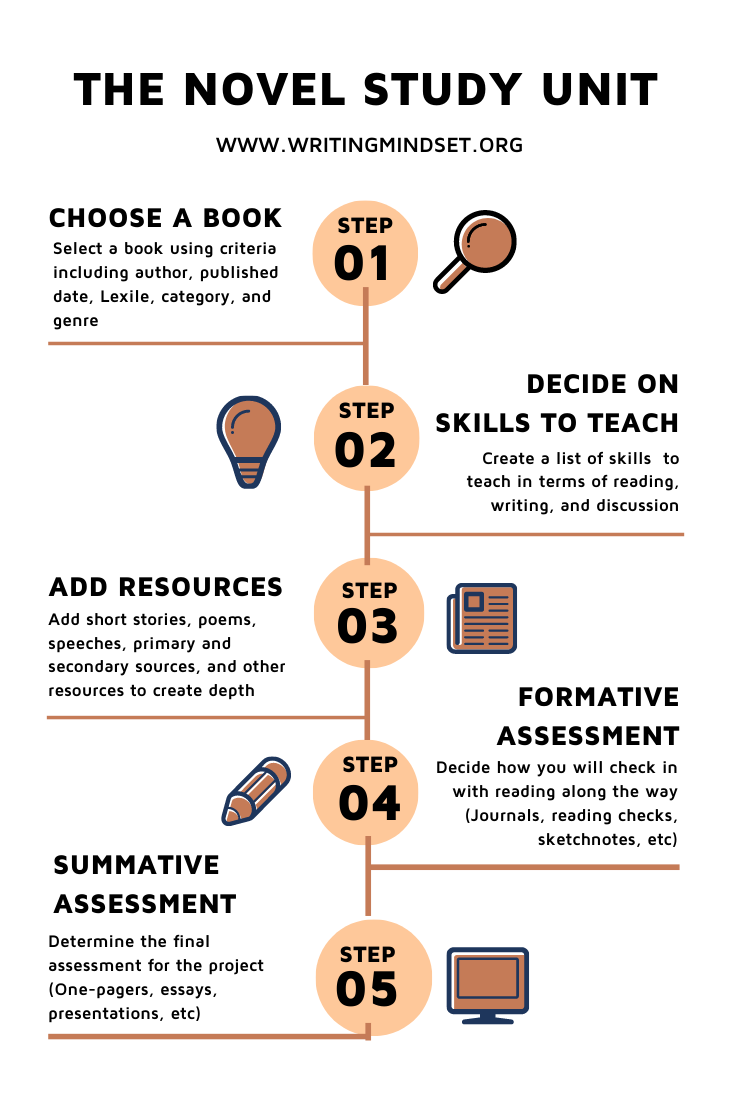

Overview of Novel Study Unit Design:

Start With Planning

What is a Novel Study? What Else Am I Doing Besides Novel Study?

The novel study is when an entire group or class is reading and experiencing the same book together. This is different from book clubs and literature circles because it involves the entire group. When I am not doing a novel study, our class is focusing on independent reading, the short class read alouds, the extended class read alouds, poetry analysis, mentor text work, small group reading, and book clubs. I always return to independent reading because I want to foster that time with my students and let them read. Independent reading time is some of the most important time spent in class with my students. However, because I only have 58 minutes each day, sometimes we insert other reading modalities during this time. It also keeps my teaching fresh and new for students. There is a balance between the necessary routine and crucial spontaneity.

How Often Do I Do Novel Units?

In my district, high school students change classes every 12 weeks. Middle school, on the other hand, keeps the same core classes all year long with grades being due every six weeks. Some of my district’s high school classes are designed completely around novel studies. Meanwhile, my middle school curriculum follows a standard model of reading a certain text and most often responding to that text in writing. For each of my sixth-grade classes, at least three of these marking periods incorporate novel reading where we are all reading the same book together. Currently, here are the whole-group novels selected for each of my classes:

Advanced English:

Ghost Boys by Jewell Parker Rhodes

Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry by Mildred Taylor

Uglies by Scott Westerfeld

Boys Without Names by Kashmira Sheth

General English:

Ghost Boys by Jewell Parker Rhodes

Iqbal by Francesco D’Adamo

Maniac Magee by Jerry Spinelli

Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds

Step 1: Choose a Book

What Book Will You Teach? Why?

Some districts will outline what text to teach in their curriculum or pacing guide. Some districts will allow teachers the freedom to choose their novels. In my experience, a lot of this depends on the building and district resources. It is all about what is in each building’s book rooms. It also depends on the resources the teacher is finding for their classroom. My classes will be doing an extended read aloud with The Bridge Home by Padma Venkatraman because I created a project on the teacher donation website, DonorsChoose.Org. They will have access to this book in my class because I am using it as a supplementary text that I got through donations. How books come to be in classrooms often determines what books are taught to students. It goes without saying that we need to be diligent regarding current, relevant, and diverse texts in our classrooms. It is not enough to simply have these books; the best part of the novel unit design is figuring out how we will teach these books to our students. A great article to check out on this topic is Tricia Ebarvia’s post, “Why Diverse Texts Are Not Enough.”

I outline many of the variables and considerations for choosing books in my post, “10 Criteria for Choosing Diverse Texts for Your Classroom” including author, published date, Lexile, category, and genre. I know that the aspect of Lexile always starts a great conversation, but I find that particularly with the whole group novel study, I need to be mindful of Lexile because it will then influence the design of my daily lessons and formative assessments. At the end of this post, I outline an example unit with Iqbal by Francesco D’Adamo Lexiled at 730. For my students who are striving readers with fluency and comprehension as areas of concern, they will not be able to read this book on their own. So, I can design multi-leveled reading groups, but I need to steer away from the independent assigned reading. It wouldn’t be fair for me to assign and assess them on reading above their level. All aspects of the book must be considered to make sure it is the right fit for your group of students.

Step 2: Decide on Skills to Teach

What Skills Will You Teach? What is the book’s purpose?

A great starting place to think about what skills you want to teach with each novel is to read the scope and sequence outline given by Kelly Gallagher and Penny Kittle in 180 Days: Two Teachers and the Quest to Engage and Empower Adolescents. On pages 69-73, I found the year-at-a-glance interesting because it reminds us that teaching novels need to have a purpose outside reading it together. Both Gallagher and Kittle go on to outline the essential questions they have for each book, the skills identified during the course of teaching the novel, and other mentor texts or book talks that will need to be considered when working with the novel or anchor text.

I break down the skills I want to teach in terms of reading, writing, and discussion. I ask these guiding questions:

What do I want students to understand in their reading of the text?

These can be things like character traits, plot elements, Notice and Note signposts, etc.

What do I want students to learn with their written work on or in the reflection of the text?

These can we things like how to organize a paragraph, how to write a claim, how to insert snapshots into their writing of personal narratives, etc.

What do I want students to think about? What can we discuss?

These can be things like big-picture thematic work, historical analysis, social justice issues, etc. It can also include HOW we can teach them to speak to one another in a small group format or in a whole group format.

Using these questions helps build a framework for what I am teaching with one book in particular. It is too easy to want to teach ALL the skills ALL the time in EVERY class. I rather teach fewer skills and get mastery rather than too many and create confusion.

Step 3: Add Resources

I love this part! It is like adding the seasoning during cooking. I am constantly on the lookout for mentor texts to talk about with my students, books that I can book talk, and other writing in a variety of genres that can provide meaningful connections. Other texts in a variety of genres provide dimension to the novel unit in ways that just a singular text cannot offer on its own. If we are reading historical fiction, I will try to pull a variety of primary and secondary sources to help facilitate student understanding. If we are reading something along the lines of realistic fiction, I will try to pull accompanying texts that deal with similar issues. The goal is to expand student reading experiences in all directions. Here are some ideas for supplementary texts:

Short Stories

Poetry

Photographs

Primary and Secondary Sources

Memoir Excerpts

Picture Books

Graphic Novels

Video Clips/Speeches

Diary

Similar Anchor Text

Places like NewsELA, CommonLit, and TweenTribune are great places to start looking for these sources if your curriculum does not offer enough current, relevant, and diverse options.

Step 4: Formative Assessments

How Will I Assess Knowledge While Reading?

In my post, “Ways to Conquer Three Types of Assessments (So, I'm Not Taking Papers Home)” I talk about many different ways I assess students during instruction (formative) and after instruction is over (summative). I know many teachers are fans of reading guides that are copied and dispersed with the novel during novel units. I am not discouraging this because if it works in your classroom, it is important. All teachers should feel confident about what they are teaching. There are factors of engagement and accountability to consider when designing formative assessments. However, I have strayed away from this worksheet and book model. I simply don’t want to grade worksheets, and I feel like students have better ways to demonstrate their thinking while reading.

Instead, I am using more reading journals as ways to reflect after reading. These reflections can be electronic on Google Classroom or in their classroom writing journal; however, the goal is to get them to respond in big ways after we read a chunk of the text together. I also like many of the other forms of formative assessment listed below. The goal is and should always be: How do I assess student knowledge in the present moment rather than taking that student knowledge home in my grading bag?

Example Formative Assessments:

Reflection Journals (Or as Lisa Moore Ramee in A Good Kind of Trouble might say...eyeball journals)

Quick Writes or Quick Draws

Peer Reviews with Flipgrid

Class Discussions and Q&A Discussion Techniques

Think/Pair/Share

Thinking Maps/Sketchnotes/Visual Thinking Strategies

Annotation Checks

Verbal or Written Summaries

Stations or Centers

Google Classroom Questions/Entry Logs

Step 5: Summative Assessment

How will I Assess Knowledge After Reading?

For the majority of my career, I would have inserted an essay after the book reading. While I still teach the standard essay, I am also incorporating a variety of other means to assess students after they read. I love one-pagers as a visual means, and when I did the TED Talk unit with my students, it provided insight into who my students were that I would not have seen in an academic essay. Now, my goal is to make sure that I am not stifling my students with feedback on standard papers, and I get to understand their thinking. The summative assessment should align with the reading, writing, and discussion goals. It should also be figured out before the unit starts so you are working toward it the entire time. I like to show examples along the way so when you roll out a project it doesn’t seem like a massive undertaking. If I do show them how to do an essay, I make sure they know this is one form of an academic response. People thinking about books don’t always respond in essays after they read them.

Example Summative Assessments:

Essay

One-pager sketch notes

Write a scene from the novel that does not exist

Passage Analysis

Google Forms Reading Check (Quick Formative Assessment Grades)

Research Projects/Inquiry Projects

Letters

Outlines

Performance/Speech/TED Talks

Example Novel Unit for General English 6

Main Novel/Anchor Text: Iqbal by Francesco D’Adamo (730 Lexile)

Supplementary Texts:

“A Schoolgirl’s Diary” from I Am Malala by Malala Yousafzai and Patricia McCormack (Memoir Excerpt)

“I Have a Dream” by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (Speech)

“The First Day of School” by R.V. Cassill (Short Story)

“Harlem” by Langston Hughes (Poem)

“Speech to the Young: Speech to the Progress-Toward” by Gwendolyn Brooks (Poem-Theme Introduction)

Essential Questions:

How do I identify plot elements?

How do I find the theme?

How do I complete a nonfiction summary?

How do I identify the main idea and details?

How do I organize a paragraph response?

(Topic sentence and supporting details)

How do I collaborate with other writers in a workshop?

Key Reading Vocabulary: Protagonist, Antagonist, Exposition, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, Resolution, Theme, Conflict, Setting, Character Traits: Inside and Outside

Key Writing Vocabulary: Topic Sentences, Supporting Details, Concluding Sentences, Claim Statement, Compare, Contrast, Primary Source, Secondary, Source, Cite

Mentor Text Focus Areas: Compound Sentences (But, And, So), Onomatopoeias, and Personification

Novel Reading Goals:

Analyze character traits (reinforces work from the second marking period with adjectives and snapshot writing with personal narratives)

Sequence plot elements

Identify theme

Discussion Goals:

Identify what is child labor

Discuss the role of child labor in consumerism

Connect social injustices to activism

Writing Goals:

Introduce research with studying people

Create a biographical report on a chosen person or a “change-maker”

Practice paragraph organization

Example Novel Unit for Advanced English 6

Main Novel/Anchor Text: Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry by Mildred Taylor (920 Lexile)

Supplementary Texts:

Excerpts from A Young People's History of the United States: Columbus to the War on Terror (For Young People Series) by Howard Zinn and Rebecca Stefoff (Historical Non-Fiction)

“I Have a Dream” by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (Speech)

“The Gold Cadillac” by Mildred Taylor (Short Story)

“I, Too” by Langston Hughes (Poem)

“Speech to the Young: Speech to the Progress-Toward” by Gwendolyn Brooks (Poem-Theme Introduction)

Essential Questions:

What should I notice and note while reading a fiction text?

How do I find the theme?

What strategies could be used to generate, plan, and organize ideas in my writing? (pre-writing/organization)

How do I make a claim?

How do I organize an argumentative essay?

How do I collaborate with other writers in a workshop?

Key Reading Vocabulary: Protagonist, Antagonist, Exposition, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, Resolution, Theme, External Conflict, Internal Conflict, Setting, Character Traits: Inside and Outside

Key Writing Vocabulary: Argumentative: Introduction: Hook, Summary, Claim Statement, Body Paragraphs: Topic Sentences, Introduce Evidence, Cite Evidence, Explanation/Elaboration, Conclusion

Novel Reading Goals:

Analyze character traits (reinforces work from the second marking period with adjectives and snapshot writing with personal narratives)

Sequence and analyze plot elements (Notice and Note)

Identify theme

Discussion Goals:

Identify historical timeline in book setting (Civil War to Civil Rights timeline project)

Compare and contrast historical racism and modern racism

Connect social injustices to activism

Writing Goals:

Review paragraph organization

Identify a claim statement

Support a claim with reasons and evidence from the book